You can tell the difference between a look and a stare. Sometimes it’s a short series of not-so-subtle glances, other times it’s a fixed unwavering gaze, so cold and intrusive, that if it spoke it would almost certainly demand, “explain yourself!”.

For people who have facial disfigurements and visible differences, being stared at can be a daily occurrence. Like many people born with a craniofacial condition, the visibility of my cleft has fluctuated over the years, and with that, so have the levels of attention I’ve received. During my adolescence, my facial disfigurement was hyper-visible, I would often get intrusive looks, stares and even abusive comments when out alone or in unfamiliar company.

Sometimes, having a facial disfigurement means always being stared at, but never being seen.

I recall one occasion when I was sat outside a café. I was stared at so persistently by one individual, that even when I deliberately moved out of their sight, they too moved in order to get a better view of me. It’s an experience that is enough to make anyone feel insecure, let alone a person who had to endure this kind of reaction on a daily basis. I was quite young at the time, so I didn’t have the confidence to confront this person. Also, for someone with a facial disfigurement, staring can sometimes be the beginning of a situation that escalates into verbal or physical abuse, which can make any confrontation risky.

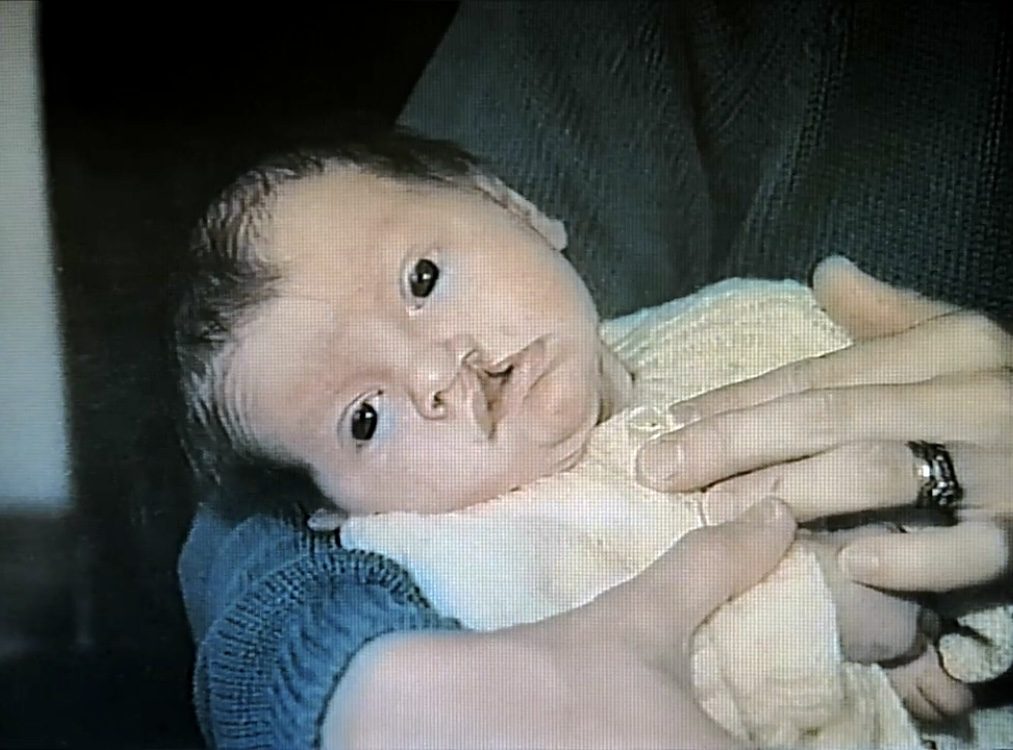

Ryan has a cleft and experienced intrusive stares and abusive comments when he was young.

On the rare occasions I’ve spoken about these countless experiences, I find that people don’t often understand. Staring may seem mild or even benign, but these small casual acts of disrespect accumulate daily, they exhaust you, and are part of a wider experience of prejudice and discrimination. From erasure across culture to demonisation in media, we are acutely aware that many people don’t accept us, and being stared at can be a reminder of that attitude.

Many of us have been told we don’t belong, so a stare can feel like someone saying, “what are you doing here!?”. You get gawped at by people who don’t understand you. Sometimes, having a facial disfigurement means always being stared at, but never being seen.

Research released by Changing Faces has shown that people with visible differences have experienced an increase in hostile behaviour when they go out in public, with a rise from a third (34%) in 2019 to over two in five (43%) in 2021. The research also revealed that this was having a negative impact on the mental health and wellbeing of people with a visible difference, with half of respondents (51%) citing that they have felt self-conscious or embarrassed as a result of their visible difference. A quarter (25%) report feeling isolated and lonely because of their visible difference.

Treating people with basic respect is not an unrealistic expectation.

In order to see a reduction in behaviours like staring, I believe we must first address how dismissive people can be of its very occurrence. Many are tempted to put these reactions down to nature, “it’s just human nature”, they say. Whilst it is true that we all do look at each other and have curiosity for anything unfamiliar, we have to be careful that we don’t justify or excuse preventable harm. Everything we humans do, by definition, is ‘human nature’, so stating it serves no purpose here, other than to end the conversation. It’s another way of saying, “this is unstoppable. Get used to it”.

But why should we? We all know staring is rude and disrespectful, so to believe that people like me are somehow ‘destined by nature’ to be stared at, is to consider us as being too difficult to respect. Thinking this is not only naive, but also callous, insulting and discriminatory.

Rudeness is not inevitable and treating people with basic respect is not an unrealistic expectation. This defeatist attitude also absolves the person staring of any responsibility of wrongdoing, whilst encouraging them to remain apathetic and not reflect on their behaviour. Blaming nature for this is not wise or philosophical, it’s passing the buck. Whilst it may be beneficial for an individual with a visible difference to be prepared for people noticing them, we must not get into the mindset that this behaviour is unstoppable or even ok.

People with visible differences should not have to expect to be treated differently.

Dismissive reactions aren’t always quite so cavalier. Sometimes people will deny a person’s experience of being stared at because they just don’t want to believe the public can be that rude and unkind. Sadly, people with visible differences and disfigurements don’t have the luxury of that illusion, so it’s important that you believe us.

Nowadays, I still do get stared at, but not as often as I used to. Sadly, this is not due to a change in society, but because my appearance, whilst still visibly different, conforms more to societal norms than it used to. People who ‘look different’ have an appearance that lacks the privilege of being normalised, and it is this that leads to prejudice, discrimination and general mistreatment, which includes staring.

I believe that the main way to tackle this problem is through awareness and representation. People often stare at what they consider to be unfamiliar, so if those with disfigurements and visible differences were better represented and recognised as a legitimate part of society, the temptation to stare would decline.

As Katie Piper says, “all normal is, is something we see often”. Being aware that people may look different to you and being okay with that simple fact is very important. There is no need to stare, if you truly accept and embrace difference.

So, what is the difference between a look and a stare? The difference is respect.

This week is Face Equality Week, and our theme is staring. We’re calling for the public to better understand the impact of negative behaviours, such as staring, on those who have a visible difference or disfigurement. Please share our film to raise more awareness of staring.