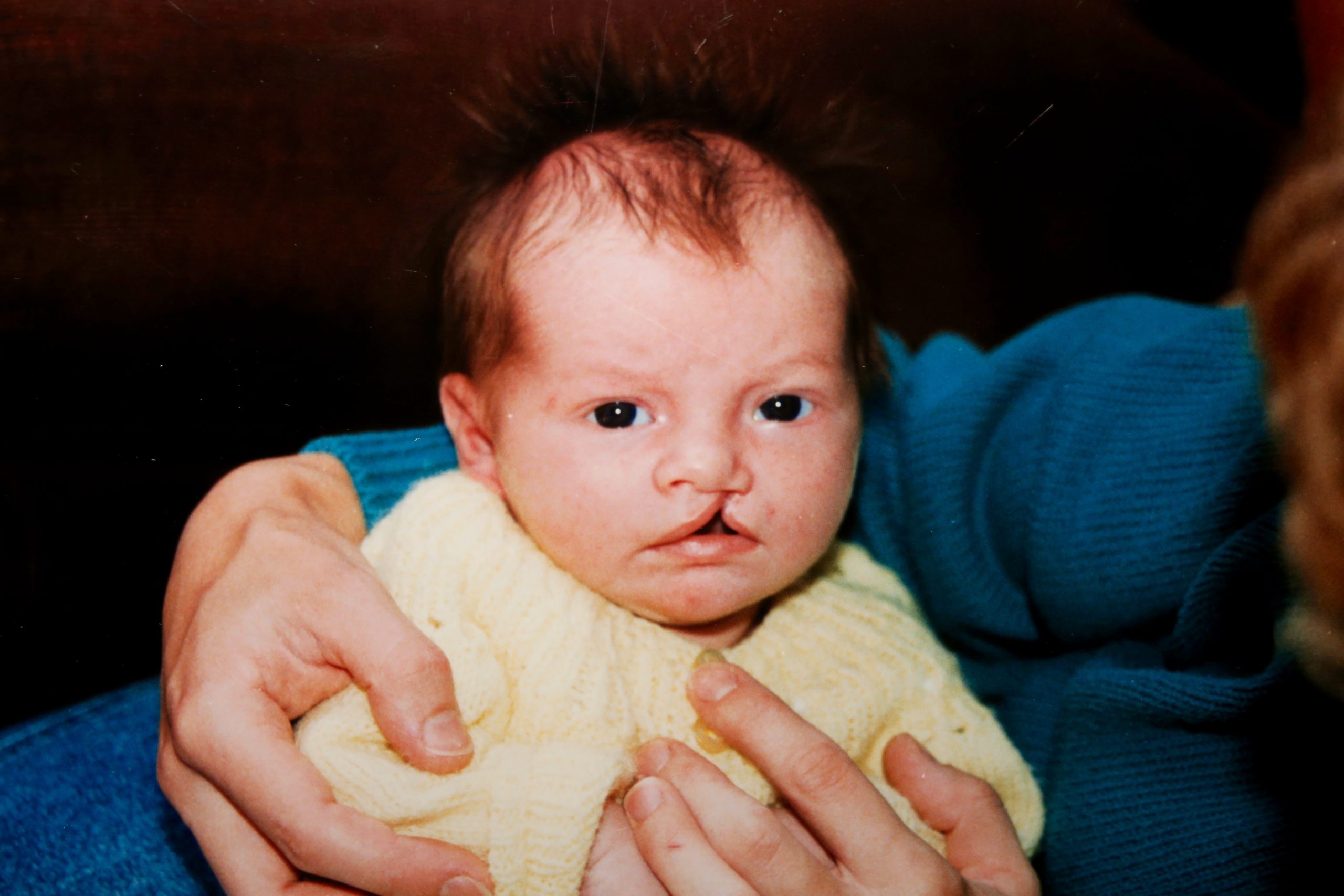

I was born with a cleft lip and palate. As a child, my difference was noticeable but not hyper-visible. However, during my teenage years my appearance began to change. My disfigurement became much more noticeable and to my surprise, the impact of these changes was not just aesthetic.

It began slowly. I would get the occasional inappropriate comment from members of the public. Eventually it got to a point where every time I went out there would be an incident; a lingering stare, a mumbled remark, and occasionally people shouting insults. Not necessarily everywhere I went, but enough to make me think twice before leaving the house.

The world was no longer a welcoming place. It was a really difficult time. In terms of my body image, these negative experiences affected my self-esteem and life choices. I became withdrawn and fearful of participating in life. Even after my successful reconstructive surgery many of these psychological issues still remained.

There was a time when I thought surgery was the answer. After all, disfigurement is often seen as an aesthetic issue, so I’d be forgiven for thinking an aesthetic remedy like surgery would suffice.

Ryan was born with a cleft lip and palate.

However, while disfigurement can be reduced, altered, and camouflaged – very rarely can it be erased. I soon found that figuring out how to be OK with who I am was a far more sustainable way of reaching contentment.

I sometimes get asked if I have any advice for anyone affected by a cleft. I never know what to say because everyone’s needs are different, so I instead tell them the advice I’d give to my younger self, “Learn to question the ideas that cause you shame.”

There is nothing inherently traumatic, bad or sad about having a cleft. However, when our natural state of being is different from what we’re “expected” to be, the way the world can react can be very traumatic.

For me, the greatest challenge of living with disfigurement was learning to change how I felt… NOT how I looked. Challenging the harmful attitudes toward facial disfigurement was key to my self-acceptance.

Sometimes it’s really hard. There are a lot of attitudes, people and practices in our culture that are actively hostile towards disfigurement.

You’re encouraged to treat your cleft like an untenable flaw, rather than a legitimate part of who you are. You don’t often see yourself reflected in culture; except as outdated storytelling tropes where disfigurement is synonymous with evil and tragedy.

You may also encounter the soft bigotry of low expectation, which will try to tell you that having a facial difference means you can’t have the life you want.

Challenging the harmful attitudes toward facial disfigurement was key to my self-acceptance.

However, over time it gets easier. Soon you will begin to recognise that you are valid, disfigurement is ok, and beauty is far more varied than we’ve been led to believe. So question the ideas that cause you shame. All this shame was projected onto you, it doesn’t belong to you, so let it go.

My hope is that disfigurement will be recognised as a legitimate part of someone’s identity. I believe the approach must be holistic. It’s ok to passionately support reconstructive surgery, but we must not neglect the importance of challenging the negative way we think about disfigurement.

If we don’t, then people who live with conditions that affect their appearance will always be unnecessarily burdened by harmful, life-limiting attitudes – no matter how many surgeries they have.

I want to speak out as a campaigner so my personal experience can be put to positive use. I feel it’s my duty to pass on as much information as I can, to help create an enlightened society that fully accepts and values people however they look.