Ellie’s experience (TW: self-harm):

While not everyone with a visible difference identifies as disabled, many can be significantly disabled by societal attitudes and stigma. In the context of sport, this can sometimes be painfully clear.

A visible difference that does not affect your physical performance should, in theory, not be a barrier to making a sports team or taking part in a physical activity, but all too often society says no – if not actively, then passively.

My visible difference comes from decades of mental illness and a history of self-harm. I have scars all over my body, some in concealable places but some in less easy to conceal places such as my legs, arms and face. Although self-harm is less of an issue for me nowadays, I will live with the visible reminders for the rest of my life.

For well over a decade, I covered all my scars. I even had special dispensation for a long-sleeved uniform when I worked in a hospital. I was so worried that if anyone saw them, they would judge me and my abilities. Body image was always a struggle for me.

However, I didn’t anticipate that along my journey I would fall in love with hula hooping! A friend dragged me along to her hooping class. I was very reticent as I didn’t like to do anything that drew attention to my body, plus I could never do it at school. To my surprise, I found that adult hoop dance is totally different to playing with the flimsy plastic hoops we had in the playground.

The openness of the circus community massively improved my confidence and acceptance of my own visible difference.

The first six months of my hoop journey were mainly spent in my bedroom, where no-one could see me, learning new moves from YouTube videos. I’d learnt early on that hoops are easier to control on bare skin than slippy clothing, but I couldn’t do this anywhere but my room because I was worried about my scars. I soon encountered the issue of there not being enough space though. If I lost control of my hoop, then I also lost several ornaments and even once a light bulb!

The lure of hooping outside in sunny parks with my new-found hoop friends was ultimately stronger than my fear of people seeing my scars. I took the plunge and started to hoop outside with more suitable clothing on. I soon realised that no one was looking at my body, they were looking at the hoop and its movements.

I quickly gained confidence and learnt more about how to perform, which only added to my new-found confidence. Hoop dancers generally don’t choreograph their dances – we enter a state known as “flow” where we become mindfully at one with the music, the hoop and our bodies. When I’m in flow, I don’t think about my scars, and I find that nobody else notices them too.

When I am doing sport, I am free.

The circus community is generally very diverse and accepting. People come from many different backgrounds and enjoy wearing wacky and colourful clothing. Tattoos and body modifications are quite common, so having scars is nothing unusual. The openness of this community massively improved my confidence and acceptance of my own visible difference.

Over the years, I took up other circus disciplines such as acro. I also took up roller skating, which has a similarly accepting community. In roller skating – particularly at skate parks which is my favourite type of skating – people judge you by how much effort you’re putting in, what you bring to the floor and if you can “send it” (even if it goes wrong!). Mistakes are accepted as part of the process – there are always a couple of people with big bruises or maybe other injuries from a failed attempt at a trick. 9 times out of 10 people presume my scars are skate-related and I leave it at that.

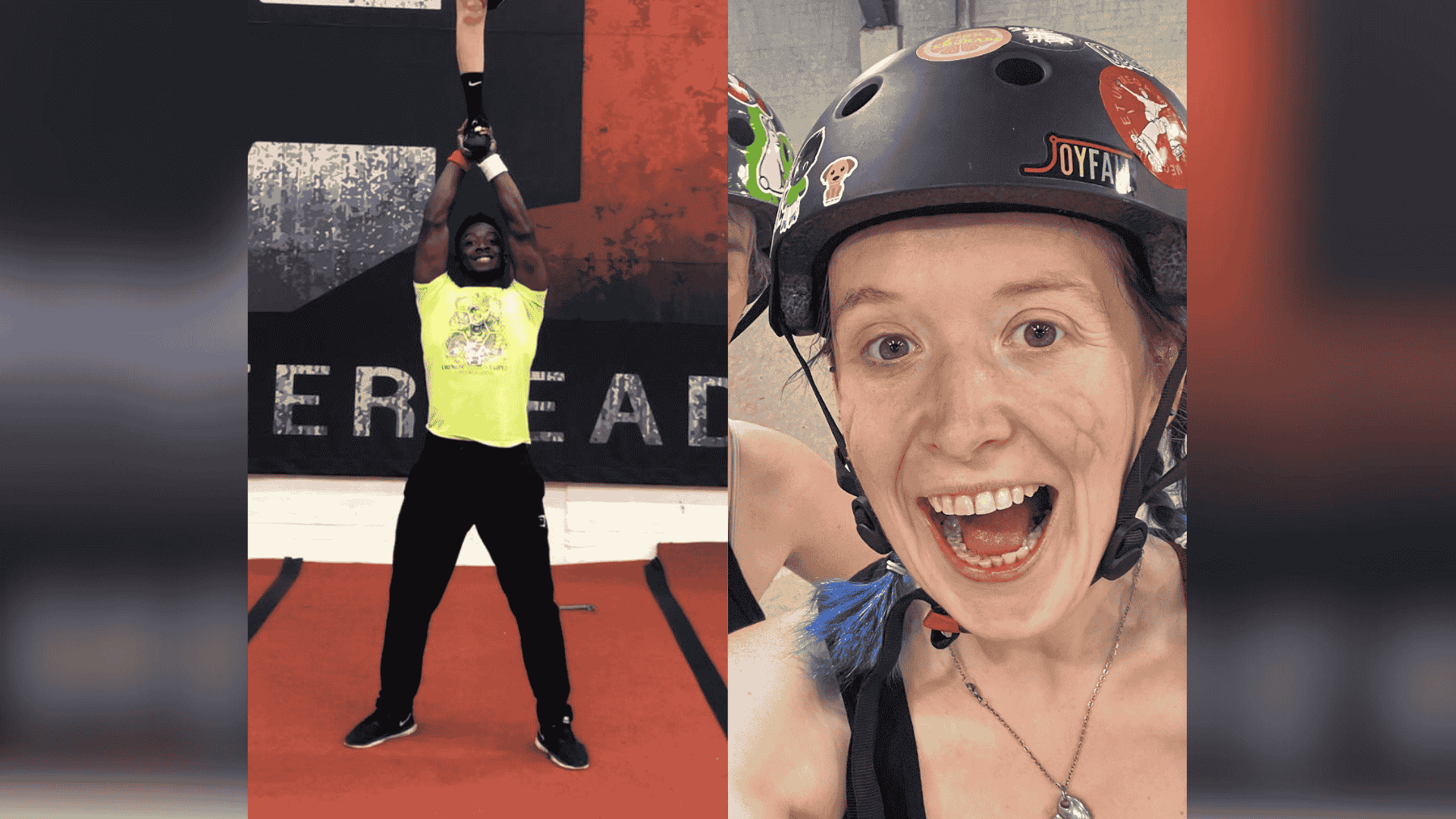

Roller skating has been another outlet for Ellie to express herself

Unfortunately, the wider world sometimes still has issues with my scars. The skate community relies on Instagram to network and connect, as well as showcase our skills, but I have had my videos or photos blocked by Instagram on numerous occasions as “inappropriate content”. This meant that even after a couple of years of growing my confidence, I still felt that sports such as running or going to the gym were off limits.

I was aware the sports I was taking part in were full of people who enjoyed being outside the conventional norms of society. I also knew I had a certain level of skill at hooping and skating that protected me somewhat from people seeing my scars before my performance. It took several years before I had the confidence to feel that I could appear “good” enough to be able to be out running or at the gym despite my scars.

Over a decade later, I now don’t feel like my scars come before myself in a physical activity setting. I can now wear a crop top when I’m out running or at the gym, enabling me to choose the clothes that are best suited to the sport I’m doing, rather than what conceals me. When I am doing sport, I am free.

Romeo’s experience:

Sport has a unique way of transcending the boundaries of our daily lives, offering not just physical benefits but emotional and psychological growth as well. Stepping into the world of sport can feel like an act of bravery, and be a powerful tool to build confidence, foster resilience, and inspire others.

Building this confidence can feel like a mountain to climb, but once achieved, it creates a profound sense of empowerment.

I have burns on my neck, chest and stomach, which are often visible during the sports I’m involved in – football and cheerleading. One of the most challenging aspects of sport is the vulnerability it demands. Whether it’s simply being in a changing room environment, stepping onto a football pitch, or competing at a cheerleading competition where points are awarded based on performance, presence, and often, appearance. Sport leaves you exposed. For someone with a visible difference, this exposure can feel daunting, even overwhelming. Yet, it is within this environment that sport becomes an enabler for growth.

In cheerleading, where aesthetics are integral to the performance, there’s a pressure to conform to certain ideals of beauty, often amplified by uniforms and makeup. This can be challenging, but it also offers an opportunity. By showing up authentically and daring to take the floor, you become a beacon of courage and empowerment. You challenge norms, redefine standards, and inspire others to embrace themselves.

Sport doesn’t just teach you how to play a game; it teaches life skills. Teamwork, communication, leadership, and perseverance are qualities that extend far beyond the pitch or the mat. When you’ve faced the challenge of showing your true self in sport, you carry that confidence into every aspect of life, whether it’s at work, in social settings, or in personal relationships.

Football and cheerleading has helped Romeo build resilience

I’ve found that football, with its emphasis on team dynamics, has helped me to understand the importance of collaboration and trust, even when I felt self-conscious about being in such an exposed environment. Cheerleading, on the other hand, taught me precision, discipline, and the ability to stand tall under scrutiny. Both sports demanded resilience, and in return, they made me more resilient.

In both football and cheerleading, confidence is a direct contributor to performance. A cheerleader’s presence on the floor, every move and expression, is amplified by their self-assurance. On the football pitch, the way you hold yourself, communicate with teammates, and make decisions is underpinned by belief in your own abilities. Building this confidence can feel like a mountain to climb, but once achieved, it creates a profound sense of empowerment.

Sport also builds something even more important than individual confidence; it fosters community. Being part of a team creates a sense of belonging that can help counter feelings of isolation. Seeing teammates who accept and celebrate you for who you are fills you with courage. It doesn’t just uplift you; it provides a platform to inspire others. By participating in sport, you show others with a visible difference that they, too, can take up space, succeed, and thrive.

Sport isn’t just about competition; it’s about connection, growth, and empowerment.

Resilience is a hidden strength that sport encourages. Losing a match, missing a stunt, or facing a tough opponent teaches you to bounce back. This resilience can translate into navigating a world that often fails to accommodate difference.

Every time I step onto the pitch or the cheer floor, I’m reminded that sport is so much more than physical activity, it’s a platform for self-expression, a source of confidence, and a vehicle for change. For those of us with a visible difference, sport can be a place to rewrite narratives, to show the world that beauty, strength, and capability come in all forms. And, just as importantly, it’s a chance to inspire others with a visible difference to embrace who they are, both on and off the field.

Sport isn’t just about competition; it’s about connection, growth, and empowerment. To anyone with a visible difference considering sport, I say this: take that first step. You’re not just stepping into an arena—you’re stepping into your power.